Appointed in 1933 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt as America’s first female secretary of labor (and the first woman to hold a cabinet position), sociologist and workers-rights advocate Frances Perkins had her work cut out for her.

A New Deal was promised to Depression-weary Americans, and it was Perkins whom Roosevelt relied on to craft signature legislation.

When the president signed the Social Security Act in 1935, it was Perkins who could take credit for having developed and then shepherded the landmark law through Congress. Unemployment insurance and the minimum wage were also social welfare issues she championed.

Yet these professional successes belied the difficulty “The Woman Behind the New Deal” faced when forced to navigate Washington, D.C.’s entrenched social and political culture, whose key players expected a woman to support her husband’s career by making social calls and hosting dinner parties. But what if the woman is the one with the career?

Enter Mary Harriman Rumsey, who suggested to Perkins—and proved to Washington’s establishment—that a surprising option was at the ready.

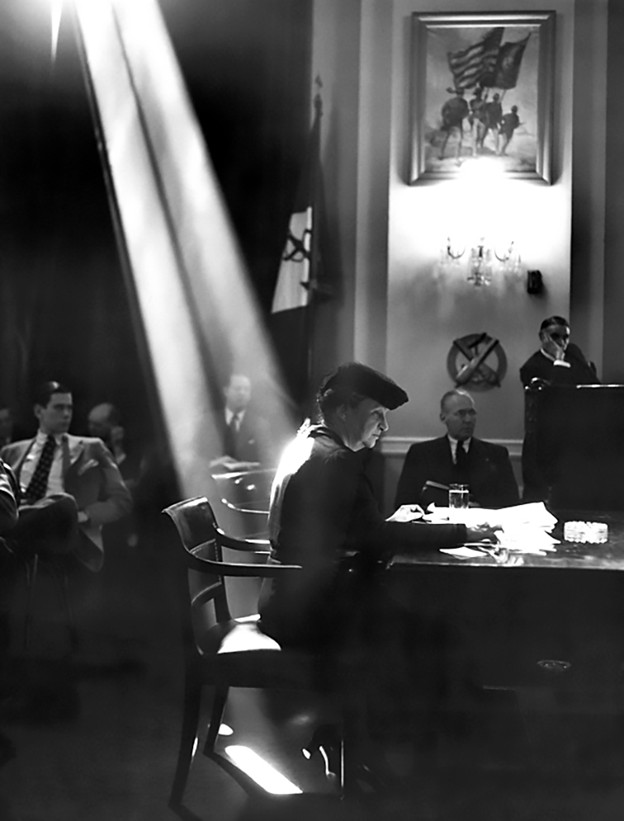

IMAGE Francis Perkins testifying before the Naval Affairs Commission BETTMANN/CORBIS